The right practice at the right time

Musicians with perfect pitch (a proxy for "musical talent") have a particular anatomical asymmetry of the planum temporale within the cortex of the brain, as shown by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Most professional musicians do not have perfect pitch. But a few do. (Mozart is said to have had perfect pitch. ) And apparently no amount of practice can produce the kind of anatomical asymmetry in the brain that facilitates perfect pitch. At least not later in life. There's speculation that the right kind of practice at the right time--early in life, when the brain is most plastic--might lead to these kinds of changes.

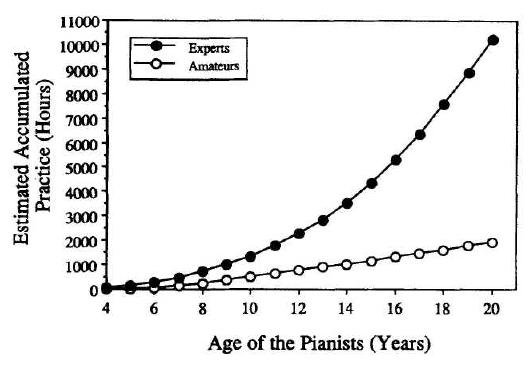

The brain remains malleable throughout life and it's that malleability (or plasticity) which enables us to learn. But the brain is far more plastic in early life; before puberty. Enough of the right kind of practice can make almost any of us a master of almost anything. But there are still those who go well beyond mastery. It's widely thought that, at the least, they must have had sufficient early experience to develop the neural structures that enable for truly exceptional performance later on. And one can not rule out a genetic component.

Again, that's not to say that someone without the most propitious early developmental experiences (or genetics) can't achieve very high levels, even mastery. But they may not be able to reach the pinacle. Athletics, at the highest levels, magnifies very, very fine differences; differences too small to measure in a laboratory.

I coached world-elite athletes in an earlier life. Give me a twelve-year-old, any "normal" twelve-year-old, and I'm confident I could train him or her to become an Olympic-level athlete. But I can't necessarily say they would be the very best in the world in a highly competitive sport.

My own empirical observation, from being around two athletes each of whom dominated world competition in his own era, is that they brought a special focus to their training--and attention to detail--that the others did not. It's not so much practice as the "right" practice.

The right practice and training and mental attitude can get you awfully damn far, and well ahead of most. But it's also possible there may be one or two or a few who by virtue of better neurology, as a result of better early developmental experiences and/or genetics, will always be a bit ahead.

Sorry to be so late to this conversation. I was impressed by what Zatara had written elsewhere and was compelled to plumb around and see what else he had to say.

Musicians with perfect pitch (a proxy for "musical talent") have a particular anatomical asymmetry of the planum temporale within the cortex of the brain, as shown by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Most professional musicians do not have perfect pitch. But a few do. (Mozart is said to have had perfect pitch. ) And apparently no amount of practice can produce the kind of anatomical asymmetry in the brain that facilitates perfect pitch. At least not later in life. There's speculation that the right kind of practice at the right time--early in life, when the brain is most plastic--might lead to these kinds of changes.

The brain remains malleable throughout life and it's that malleability (or plasticity) which enables us to learn. But the brain is far more plastic in early life; before puberty. Enough of the right kind of practice can make almost any of us a master of almost anything. But there are still those who go well beyond mastery. It's widely thought that, at the least, they must have had sufficient early experience to develop the neural structures that enable for truly exceptional performance later on. And one can not rule out a genetic component.

Again, that's not to say that someone without the most propitious early developmental experiences (or genetics) can't achieve very high levels, even mastery. But they may not be able to reach the pinacle. Athletics, at the highest levels, magnifies very, very fine differences; differences too small to measure in a laboratory.

I coached world-elite athletes in an earlier life. Give me a twelve-year-old, any "normal" twelve-year-old, and I'm confident I could train him or her to become an Olympic-level athlete. But I can't necessarily say they would be the very best in the world in a highly competitive sport.

My own empirical observation, from being around two athletes each of whom dominated world competition in his own era, is that they brought a special focus to their training--and attention to detail--that the others did not. It's not so much practice as the "right" practice.

The right practice and training and mental attitude can get you awfully damn far, and well ahead of most. But it's also possible there may be one or two or a few who by virtue of better neurology, as a result of better early developmental experiences and/or genetics, will always be a bit ahead.

Sorry to be so late to this conversation. I was impressed by what Zatara had written elsewhere and was compelled to plumb around and see what else he had to say.